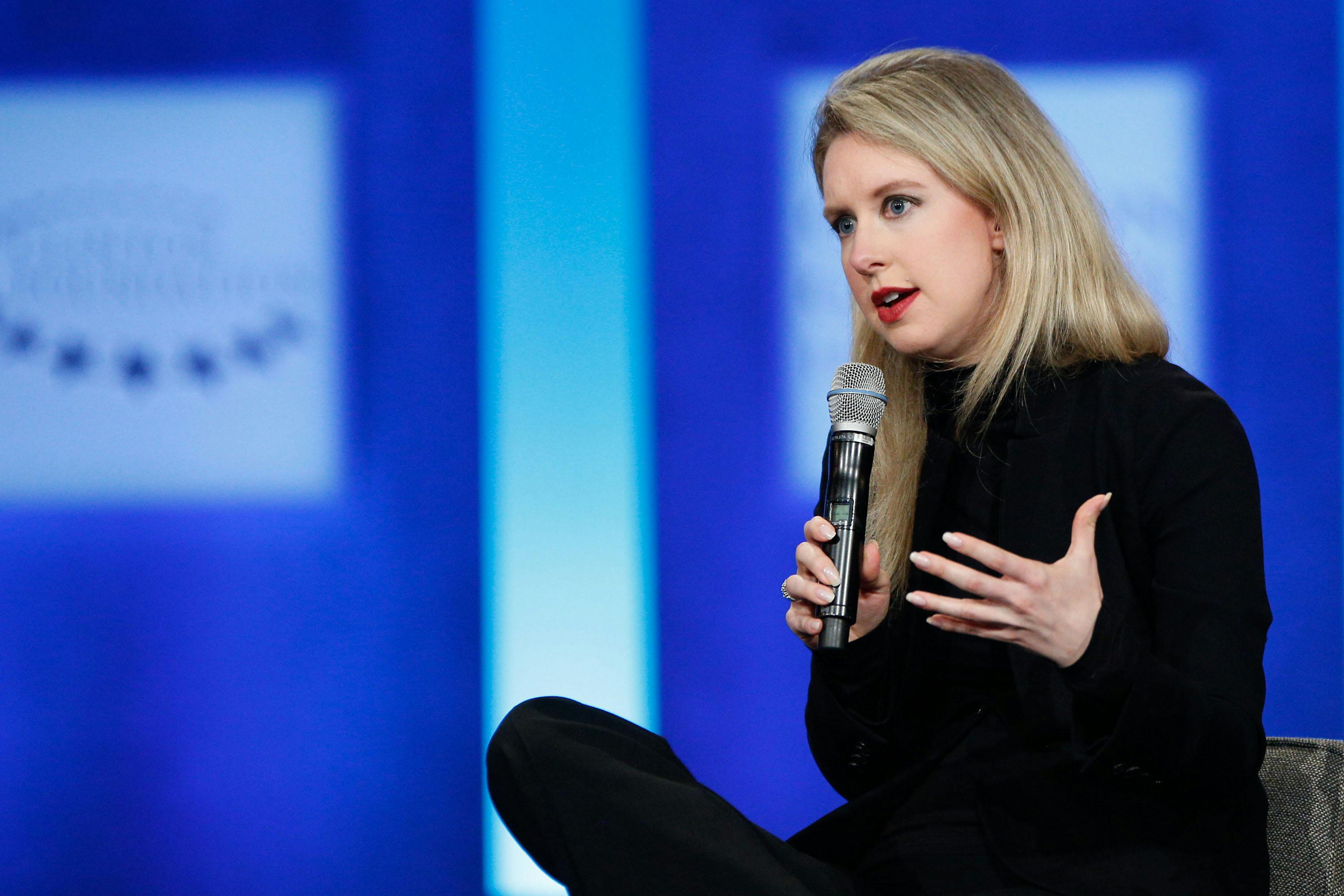

As the criminal trial of Elizabeth Holmes—the disgraced former CEO of the defunct blood-testing startup Theranos, who

allegedly defrauded investors, physicians, and patients—unfolds in San Jose,

California, rubberneckers have no shortage of content over which to obsess. The

tale of the blonde Stanford dropout who parlayed a try-hard Steve Jobs

impression into a $9 billion valuation for a company whose proprietary

technology never actually worked has been elevated to “cultural phenomenon”

status since the story first broke in 2015. Anyone wishing to catch up on the

lurid details of how Holmes went from being the darling of the business press to

the nation’s highest-profile criminal defendant has a bestselling book, a hit

podcast series, and an acclaimed HBO documentary to choose from, not to mention

an upcoming miniseries and feature film. At least two slickly produced podcasts

are now covering the trial, and reporters from multiple media outlets are

struggling to score seats in a courtroom whose capacity has been limited by the

pandemic.

The public’s fascination with the Elizabeth

Holmes saga isn’t particularly tough to understand: It’s a shocking “fake it

’til you make it” story about a firm’s staggering rise and equally dramatic

fall, amid Silicon Valley’s bonkers gold rush, with a novel spin: Theranos’s foray

into health care imbued the boom and bust with a higher set of stakes than it

might have possessed had Holmes just wanted to be a bog-standard app developer. These

media narratives correctly observe that the firm’s fraudulent lab results put

patients in danger and investors’ noses out of joint. Where they come up short,

however, is in properly contextualizing Theranos’s place within the broader

health care system. Far from hawking a “too good to be true” innovation,

Theranos peddled a toxic vision of consumer-driven medicine that no one ever

needed in the first place.

The elevator pitch that cajoled hundreds of

millions from investors’ pockets was presumably similar to Holmes’s 2014 Ted

Talk, which has since been yanked from the internet. In it, the buzzy

wunderkind recounted the story of how her beloved uncle’s untimely death from

metastatic cancer and her own paralyzing fear of needles inspired her to dream

up a way to screen for some 200 medical conditions early and often, using only

a single drop of blood from one finger prick in lieu of multiple vials from a

full-on venipuncture. Such an innovation, she reasoned, might have led to her

uncle being diagnosed much earlier, which could have lengthened his life

considerably. Holmes also emphasized that democratizing health data through

ubiquitous screening on demand, without a doctor’s orders, would produce a slew

of societal benefits: “Imagine a world in which consumers were

empowered to take any blood test, whenever they wanted, allowing them to access crucial information at the moment it really matters.”

Well! I am imagining it, and it sucks. Setting

aside a strong hunch that the type of needle phobia Holmes described was

feigned for the sake of marketing and isn’t actually particularly widespread,

the blood-test-shopping utopia that Holmes dreamed up arguably raises more

problems than it solves: As Stanford’s John Ioannidis wrote in

the Journal of the American Medical Association, catching diseases through proactive screening in the absence of

symptoms doesn’t necessarily do much to improve outcomes.

So the admittedly emotionally stirring idea

that Theranos could have saved Elizabeth’s uncle if

only he’d gotten a finger prick at Walgreens is

probably bunk. Combine that with a significant rate of false positives that

inevitably pop up when lab tests aren’t medically indicated, the risks of

overtreatment, and the fact that most blood tests don’t actually yield some

neat “yes” or “no” result and must be interpreted in context to truly deliver

high-quality care to patients, and you’re left scratching your head and

wondering what diagnostic problem Theranos was even positioned to solve.

Nonetheless, Theranos pushed hard for its

“patients-as-consumers” idyll, lobbying Arizona lawmakers to pass legislation the company practically devised itself to allow individuals to order lab tests without a physician to

facilitate the company’s big rollout into several-dozen stores. But the state’s

loosey-goosey regulatory climate wasn’t the only reason the firm zeroed in on it

as a springboard for its product: Arizona’s high rate of uninsured residents

also struck Holmes and her colleagues as a business opportunity, as they

imagined that people paying out of pocket could be enticed by Theranos’s low-priced menu and try to make do without access to primary care.

And for anyone rightfully wondering what,

exactly, an uninsured person with better access to lab testing would even do

about a diagnosis for which they couldn’t afford the treatment, Holmes had a go-to

example: Type 2 diabetes, she offered in her Ted Talk, drives some 20 percent of

national health care costs and is manageable through lifestyle changes—but

some 90 percent of prediabetic people are unaware of their status. Here, she

imagined, was a huge problem her devices could solve, if they only worked,

which they didn’t, because they couldn’t.

But let’s leave the impossibility of the

Theranos blood reader aside for a moment and examine the underlying premise. Type

2 diabetes disproportionately affects poor people precisely

because the “lifestyle changes” Holmes mentioned

are so much easier for the rich, who can better afford, store, and procure

healthy foods; prioritize exercise; and find the time and energy for both by

offsetting domestic labor onto low-paid workers. Moreover, Type 2 diabetes

drives health care costs because inequality inevitably deteriorates the health

of the poor—which is why they die more than 10 years earlier than their wealthy

counterparts. These are problems that require mass resource redistribution and

robust universal public programs to solve. Is it any surprise, then, that the

likes of Betsy DeVos and Rupert Murdoch excitedly forked over millions to

Elizabeth Holmes, who hyped “one cool trick” to mitigate the impact of poverty

as it paid off in dividends and reduced public health care spending?

It doesn’t take much to connect the dots here:

Theranos wasn’t “too good to be true,” because its product concept was an

engineering fugazi. The pesky fact that the technology didn’t work wasn’t even

the worst thing about it. If Holmes’s vision had proven to be feasible, and

Theranos kiosks offering highly accurate patient-ordered blood testing had wound up in every drug store in

the country, we’d have a world in which untold numbers of people were

emotionally manipulated into militantly surveilling their bodies for problems

they either didn’t actually have or didn’t yet need to know about—and they

wouldn’t be left any better equipped to solve whatever maladies came burbling

out of the Theranos reader. What’s more, the material causes of illness would

only get worse, as some of the richest people on earth profited off Theranos’s rise.

Elizabeth Holmes—and soon her COO and

ex-boyfriend, Sunny Balwani—now face criminal charges for defrauding investors

with the promise to disrupt the $3.5 trillion health care industry. But Theranos

perfectly illustrates why you can’t: The core problem with American health care

isn’t a lack of innovation but a lack of equitable distribution. Every

inefficiency in the U.S. health care system exists because someone is getting

rich off it, and health care entrepreneurs build their own fortunes by further

monetizing them. By ultimately failing to do so, Holmes did us all a favor.