Paul Callan is a CNN legal analyst, a former New York homicide prosecutor and of counsel to the New York law firm of Edelman & Edelman PC, focusing on wrongful conviction and civil rights cases. Follow him on Twitter @paulcallan. The opinions expressed in this commentary are his own. View more opinion on CNN.

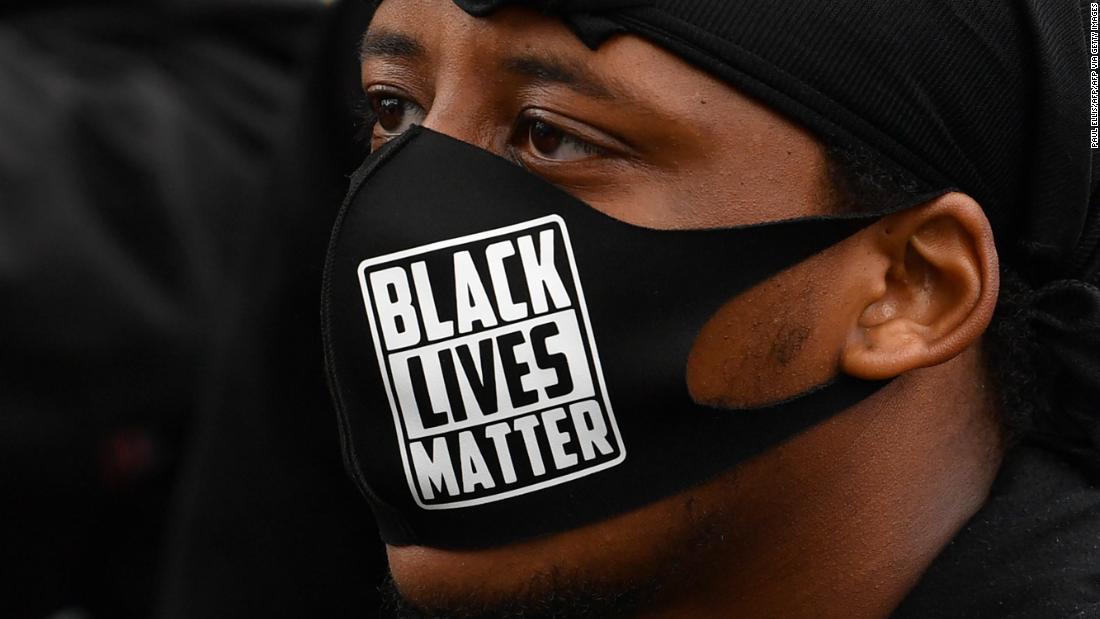

(CNN)Employees of Whole Foods, Starbucks (for a short time) and other companies have complained about being forbidden to wear “Black Lives Matter” masks at work. They believe, as many Americans do, that the First Amendment protects their right to express their political opinions on the job. After all, as the saying goes, “It’s a free country.”

Yes it is, but there are limitations. Nothing in the First Amendment confers a right of unrestricted free speech. It protects citizens from unreasonable governmental restrictions on speech. Speech restrictions by private employers are perfectly legal, as long as they are not discriminatory and do not violate federal labor and employment laws.

The words of the First Amendment are quite clear on this point:

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

Nothing in the text mentions private employers.

Businesses across the country are now confronting how to handle employees who want to express their views on politics, social justice, and other issues at work. It’s not necessarily an easy call (indeed, after initially prohibiting BLM attire, Starbucks reversed its position earlier this month). Even an employer who shares employees’ views on an issue like Black Lives Matter, for example, must think about the cost of angering or alienating customers.

The pandemic has left businesses desperate to hold on to customers, not to antagonize them. But a corporate policy viewed as racist and hostile to people of color may cause a loss of business.

Traditionally, many businesses have prohibited employees from using their clothing to express political views at work. Some likely fear that if they allow workers to wear the words “Black Lives Matter,” then other employees may show up with “White Lives Matter” and “Blue Lives Matter” masks, or even “Keep America Great” masks. Free speech cuts both ways.

Businesses may also fear that the proliferation of mask slogans will harm productivity by causing discord and bad feelings among their workers. The safest bet for big companies has traditionally been to steer well clear of politics by keeping company attire nonpartisan.

Proponents of the “Black Lives Matter” slogan counter that the words are not mere politics but a call for social justice. They view the phrase “White Lives Matter” as a sneering response by those who use their “White privilege” to oppress Blacks and other minority groups in the United States. Worse still, the phrase “Blue Lives Matters” may be viewed as an endorsement of police brutality and shootings in the Black community. Given the probability of conflicting opinions, workplace discord would appear inevitable.

It’s no wonder employers feel trapped in a swirling cauldron of racial, political and socioeconomic divisions when enforcing dress codes that never caused problems before. Enter creative lawyers who have no need to rely on First Amendment speech protections, when civil rights and race discrimination class-action theories can be stretched to obtain lucrative damage awards and protective court orders permitting the display of the prohibited slogans on their clients’ attire.

The latest example is a class-action lawsuit filed last Monday in federal district court in Boston on behalf of 14 Whole Foods workers in California, Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Washington. The lawsuit claims the workers allegedly suffered “race discrimination” and “retaliation” because they wore “Black Lives Matter” masks and other apparel at work.

The 17-page complaint alleges violations of Title IV of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. The same employees filed a complaint with the National Labor Relations Board.

Whole Foods has already signaled its likely defense that its dress code is non-discriminatory since, as reported in the New York Times, the “Whole Foods dress code prohibits visible slogans, messages, logos and advertising that are not company-related on any article of clothing” and exists to “prioritize operational safety.”

In short since everybody’s slogan masks are prohibited, Whole Foods can argue that it is not discriminating against anyone. The company said in a statement that while it could not comment pending litigation, “it is critical to clarify that no Team Members have been terminated for wearing Black Lives Matter face masks or apparel.”

Even if Whole Foods has a strong defense, class-action litigation is notoriously expensive and would subject Whole Foods and its parent company Amazon to many months or years of adverse publicity. Under these circumstances the company is likely to negotiate a swift settlement.

Regardless of outcome, this class-action lawsuit is a warning shot fired in the direction of corporate America regarding employee free speech rights in 21st century America. Like that famous rifle shot fired in 1775 in Lexington, Massachusetts, it suggests protracted battles in the years ahead over highly contentious social and political issues in the American workplace.

That reality was brought home Thursday night for anyone who may have sought the respite of baseball from the politics of Covid-19 and the Black Lives Matter protest movement.

At the season’s opener, all the players and coaches of the New York Yankees and Washington Nationals kneeled for 20 seconds while holding a long black banner before a recording of the National Anthem was played to an otherwise empty stadium. Team owners permitted players to wear Black Lives Matter T-shirts with a silhouetted Black player and an inverted MLB symbol and wrist bands.

The Founding Fathers might be proud that free speech was alive and well in the nation they created in the bloody revolution that followed Lexington and Concord. They might not have shared their enthusiasm for Dr. Anthony Fauci’s red Washington Nationals mask — or his ceremonial first pitch.