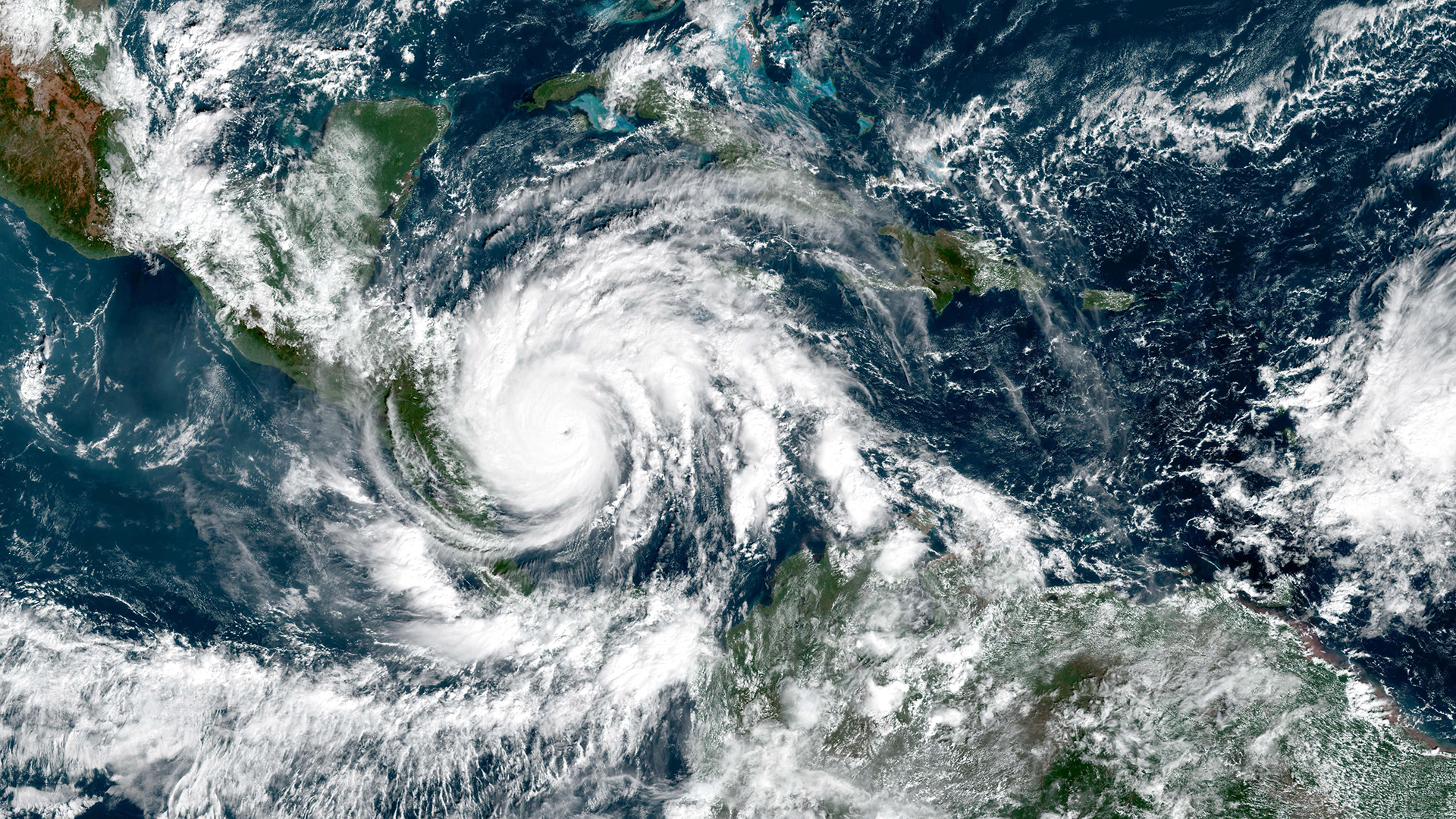

Whipping winds, torrential downpours, power outages and floods — hurricane season in the Atlantic brings a host of dramatic and dangerous weather with it.

But when exactly does the Atlantic hurricane season start and how long does it last? And what can people do to prepare in the face of the most dangerous storms on Earth? From hurricane naming conventions to staying safe in a storm, we’ll detail all you need to know about this year’s hurricane season. The 2021 Atlantic hurricane season is predicted to bring higher-than-average activity, meaning more ferocious storms.

What are hurricanes?

Hurricanes are tropical cyclones. When a tropical cyclone’s sustained winds reach 39 to 73 mph (63 to 118 km/h), it is considered a tropical storm and it gets a name from a list put out by the World Meteorological Organization. Once those sustained winds reach 74 to 95 mph (119 to 153 km/h), that storm becomes a Category 1 hurricane. According to the Saffir-Simpson scale, here are the sustained winds linked to categories 2 through 5 hurricanes:

- Category 2: 96 to 110 mph (154 to 177 km/h)

- Category 3: 111 to 129 mph (178 to 208 km/h)

- Category 4: 130 to 156 mph (209 to 251 km/h)

- Category 5: 157 mph or higher (252 km/h or higher)

Named storms of 2021

Named storms and hurricanes of 2021:

- Tropical storm Ana: May 22, northeast of Bermuda

- Tropical storm Bill: June 14, southeast of Halifax, Nova Scotia

- Tropical storm Claudette: June 17, Gulf Coast

- Tropical storm Danny: June 28, makes landfall just north of Hilton Head on Pritchards Island, South Carolina

- Hurricane Elsa: July 2, eastern Caribbean as a Category 1 hurricane

How hurricanes form

Hurricanes are the most violent storms on Earth, according to NASA. At heart, hurricanes are fueled by just two ingredients: heat and water. Hurricanes are seeded over the warm waters above the equator, where the air above the ocean’s surface takes in heat and moisture. As the hot air rises, it leaves a lower pressure region below it. This process repeats as air from higher pressure areas moves into the lower pressure area, heats up, and rises, in turn, producing swirls in the air, according to NASA. Once this hot air gets high enough into the atmosphere, it cools off and condenses into clouds. Now, the growing, swirling vortex of air and clouds grows and grows and can become a thunderstorm.

So, the first condition needed for hurricanes is warmer waters in the Atlantic Ocean, which cause a number of other conditions favorable to hurricanes.

“When the waters are warmer, it tends to mean you have lower pressures. It means a more unstable atmosphere, which is conducive to hurricanes intensifying,” said Phil Klotzbach, an atmospheric scientist at Colorado State University. “These thunderstorms, which are the building blocks of hurricanes, are better able to organize and get going.”

Another key factor: wind shear, or the change in wind direction with height into the atmosphere, Klotzbach said. “When you have a warm tropical Atlantic, you have reduced levels of wind shear,” Klotzbach told Live Science. “When you have a lot of wind shear it basically tears apart the hurricane.”

(Storms that form on different sides of the equator have different spin orientations, thanks to Earth’s slight tilt on its axis, according to NASA.)

The individual ingredients for hurricanes, however, don’t pop up at random; they are guided by larger weather systems. “There are two dominant climate patterns that really control the wind and pressure patterns across the Atlantic,” said Gerry Bell, the lead seasonal hurricane forecaster for NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center in Washington, D.C.

The first is the El Niño/La Niña cycle. During an El Niño, in which ocean water around the northwestern coast of South America becomes warner than usual, Atlantic hurricanes are suppressed, while La Niña creates more favorable conditions for hurricanes, Bell said.

The second climate pattern is the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO), which is, as the name implies, a trend that lasts anywhere from 25 to 40 years and is associated with warmer waters in the Atlantic and stronger African monsoons, Bell said.

“When this pattern is in its warm phase, or a warmer tropical Atlantic Ocean, we tend to see stronger hurricane patterns for decades at a time,” Bell told Live Science.

A warm-phase AMO conducive to hurricanes prevailed between 1950 and 1970 and since 1995, Bell said.

Hurricane outlook: 2021

Officially, the Atlantic hurricane season starts on June 1 and runs until Nov. 30. In the Eastern Pacific Ocean, hurricane season begins May 15 and ends Nov. 30, according to the National Weather Service. However, most of these storms hit during peak hurricane season between August and October, on both coasts, according to the National Weather Service’s Climate Prediction Center.

Following in the footsteps of the record-breaking hurricane season of 2020, this year is expected to pack a punch, with above-average activity forecast by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). On May 20, NOAA said there’s a 70% probability this season will bring a total of 13 to 20 named storms. Of those, six to 10 are expected to reach hurricane status, with up to five of those strengthening into major hurricanes, meaning their winds will whip up to at least 111 mph (179 km/h).

To make their predictions, scientists analyze a host of factors, from wind speed to sea-surface temperatures. Because the El Niño/La Niña cycle typically materializes in summer or early fall, forecasts done too early have limited meaning, Bell said.

The Climate Prediction Center classifies hurricane seasons as above-normal (between 12 and 28 tropical storms and between seven and 15 hurricanes); near-normal (Between 10 and 15 tropical storms and between four and nine hurricanes) and below-normal (Between four and nine tropical storms and two to four hurricanes).

Are hurricanes getting stronger?

Yes. On average, the world is seeing stronger tropical cyclones (a term that encompasses fast-rotating storms such as hurricanes and typhoons) more often than in decades past. According to an analysis of 4,000 tropical cyclones from 1979 to 2017, researchers concluded in 2020 that due to global warming these storms are not only getting stronger, but we are experiencing the strongest of the pack more frequently, Live Science reported. In another study, scientists discovered that compared with six decades ago, hurricanes that blast Bermuda are twice as strong, they reported online Feb. 12 in the journal Environmental Research Letters.

We can thank climate change for another hurricane downer: Global warming is leading to so-called zombie storms, or those that peter out and then get refueled to sort of rise from the dead, Live Science reported. For instance, in September 2020, the Category 1 hurricane Paulette made landfall in Bermuda, strengthened into a Category 2 and then weakened and died out some 5.5 days later. That wasn’t the end of her story, though, because she regained strength and reached tropical storm strength about 300 miles (480 kilometers) off the Azores Islands. And according to scientists, such zombie storms could become more frequent, as waters warm up and give once-dead storms new life, according to Live Science.

Which cities have the most hurricanes?

According to HurricaneCity, a hurricane-tracking website, here are the top 10 cities most frequently hit or affected by hurricanes since record-keeping began in 1871:

- Cape Hatteras, North Carolina: Every 1.34 years (affected by 110 hurricanes since 1871)

- Morehead City, North Carolina: Every 1.52 years

- Grand Bahamas Island, Bahamas: Every 1.63 years

- Wilmington, North Carolina: Every 1.69 years

- Cayman Islands (most affected area in the Caribbean): Every 1.73 years

- Great Abaco Island, Bahamas: Every 1.81 years

- Andros Island, Bahamas: Every 1.84 years

- Bermuda: Every 1.86 years

- Savannah, Georgia: Every 1.91 years

- Miami, Florida: Every 1.96 years (hit 75 times since 1871)

The Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale

Once a storm has wind speeds of 38 mph (58 km/h), it is officially a tropical storm. At 74 mph (119 km/h), the storm has reached hurricane levels. At that point, scientists use a 1 to 5 scale known as the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale to classify hurricane strength, with category 1 being the least severe hurricanes and category 5 being the strongest. Some scientists have also proposed adding a category 6 to account for storms that are well beyond the highest sustained wind speed for a category 5 hurricane.

| Category | Sustained wind speed (mph) | Potential damage |

| 1 | 74-95 | Minimal, with some roof leakage, gutter damage, snapped tree branches and toppled trees with shallow roots |

| 2 | 96-110 | Moderate, with major roof and siding damage; uprooted trees could block roads; power loss possible for days to weeks |

| 3 | 111-129 | Devastating damage, with gable and decking damage, many more uprooted trees and extended power outages |

| 4 | 130-156 | Catastrophic damage; roofs and exterior walls will be destroyed; trees will snap; power outages for weeks to months. Large area uninhabitable for weeks or months |

| 5 | 157 or higher | High fraction of framed houses will be destroyed; power outages for weeks to months; and huge swaths uninhabitable for same period |

Source: NOAA’s National Hurricane Center

Some scientists have argued against using just wind speed as a metric to determine a storm’s severity and potential damage, arguing that other metrics such as storm surge height or rainfall could provide better insight into a storm’s ferocity. However, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) has argued that metrics like storm surges can be hard to predict because local differences in the shape of the terrain of the ocean floor leading up to the coastline can determine the height of storm surges.

How are hurricanes named?

Hurricanes initially were named in honor of the feast day for a Catholic saint. For instance, Hurricane San Felipe occurred on Sept. 13, 1876, or the feast day of Saint Phillip, according to the National Hurricane Center. Hurricanes that struck on the same day would be distinguished by a suffix placed on the later one, Live Science previously reported. For example, a storm that struck on Sept. 13, 1928, was dubbed Hurricane San Felipe II, to distinguish it from the 1876 storm.

However, by the 1950s, the naming convention changed and in the U.S., hurricanes were given female names based on the international alphabet, according to the NHC. The practice of calling storms by female names only was abandoned in 1978.

Despite the seemingly open-ended possibilities, meteorologists do not have free reign in deciding names. The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) has a long list of alphabetical storm names that repeats on a six-year cycle. The organization aims for clear and simple names. Names are in English, Spanish, Dutch and French, to account for the many languages spoken by people potentially affected by hurricanes.

“Experience shows that the use of short, distinctive given names in written as well as spoken communications is quicker and less subject to error than the older, more cumbersome, latitude-longitude identification methods. These advantages are especially important in exchanging detailed storm information between hundreds of widely scattered stations, coastal bases and ships at sea,” the organization says on its website.

If a storm was so devastating that using the name again would be insensitive, the group meets and agrees to strike the name from the list.

For instance, people don’t have to worry about facing the wrath of a Hurricane Katrina, Ike, Hattie or Opal again, because those names have been retired, according to the NHC.

For the 2020 hurricane season, meteorologists prepared the following list of names for storms in the North Atlantic, Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico, according to the WMO:

- Ana

- Bill

- Claudette

- Danny

- Elsa

- Fred

- Grace

- Henri

- Ida

- Julian

- Kate

- Larry

- Mindy

- Nicholas

- Odette

- Peter

- Rose

- Sam

- Teresa

- Victor

- Wanda

How to prepare for a hurricane

Staying safe during the hurricane season starts with a simple step: Have a plan. People can plan for hurricanes using a simple guide at Ready.gov. Plans need to be worked out for all family members. And for those animal lovers out there, Fido and Mr. Whiskers also need an escape plan.

This plan includes figuring out how to determine whether it’s safe to hunker down at home during a storm or whether you are in an evacuation zone. If so, there is likely a specific route you should take in the event of an evacuation, as many roads may be closed, Live Science previously reported.

If you are in an evacuation zone, you also need to figure out accommodations during the storm — this could be anything from staying with family and friends to renting a motel to staying in a shelter.

Family members often have trouble reaching each other during hurricanes, so determining a preset meeting place and protocol can be helpful. Sometimes, local cellphone lines are overloaded during a storm, so consider texting. Another alternative is to have a central out-of-state contact who can relay messages between separated family members.

During a storm, pets should be leashed or placed in a carrier, and their emergency supplies should include a list of their vaccinations as well as a photo in case they get lost, according to the Humane Society for the United States. Also important is finding someone who can care for them, in the event that a hotel or shelter does not accept pets. During an emergency, they should also be wearing a collar with the information of an out-of-state contact in case they get separated from you, according to the HSUS.

How to storm-proof your home

Anyone who lives in a hurricane-prone area would do well to protect their property in advance of a flood. Because hurricanes often cause their damage when trees fall on property, homeowners can reduce the risk of damage by trimming trees or removing damaged trees and limbs, according to Ready.gov.

Another easy step is to make sure rain gutters are fixed in place and free of debris. Reinforcing the roof, doors and windows, including a garage door, is also important, according to Ready.gov.

Power generators can also be an important tool if the power is cut off for long periods of time. A power generator needs to be kept outside, as they produce dangerous levels of carbon monoxide.

People who are very serious about prevention may even consider building a “safe room” — a fortified room designed to withstand the punishing winds of a tornado or hurricane, according to the Federal Emergency Management Agency pamphlet “Taking Shelter from the Storm: Building a Safe Room for Your Home or Small Business,” (FEMA, 2014).

List of emergency supplies

People living in hurricane country also need to have a stash of emergency supplies, ideally placed in multiple locations throughout a dwelling. According to Ready.gov, a basic disaster kit should include:

- A gallon of water per person per day for at least three days

- A three-day supply of non-perishable food

- A battery-powered or hand-crank radio

- A flashlight with extra batteries

- A first aid kit

- A whistle to get help

- Dust mask

- Moist towelettes, garbage cans and plastic ties for sanitation

- A wrench or pliers for turning off busted pipes

- Maps

- A can opener for food

- And cellphone chargers

Originally published on Live Science.

Tia has interned at Science News, Wired.com, and the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel and has written for the Center for Investigative Reporting, Scientific American, and ScienceNow. She has a master’s degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California Santa Cruz, and an undergraduate degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. At the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, Tia was part of the team that produced the Empty Cradles series on preterm births in the city, which won a 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism, as well as the 2012 print award from the National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering and Institute of Medicine.