Seasonal activity is running 50 percent below normal levels.

NOAA

To state the obvious: This has been an unorthodox Atlantic hurricane season.

Everyone from the US agency devoted to studying weather, oceans, and the atmosphere—the National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration—to the most highly regarded hurricane professionals predicted a season with above-normal to well above-normal activity.

For example, NOAA’s outlook for the 2022 Atlantic hurricane season, which runs from June 1 to November 30, predicted a 65 percent chance of an above-normal season, a 25 percent chance of a near-normal season and a 10 percent chance of a below-normal season. The primary factor behind these predictions was an expectation that La Niña would persist in the Pacific Ocean, leading to atmospheric conditions in the tropical Atlantic more favorable to storm formation and intensification. La Niña has persisted, but the storms still have not come in bunches.

All quiet

To date the Atlantic has had five named storms, which is not all that far off “normal” activity, as measured by climatological averages from 1991 to 2020. Normally, by now, the Atlantic would have recorded eight tropical storms and hurricanes that were given names by the National Hurricane Center.

The disparity is more significant when we look at a metric for the duration and intensity of storms, known as Accumulated Cyclone Energy. By this more telling measurement, the 2022 season has a value of 29.6, which is less than half of the normal value through Saturday, 60.3.

Perhaps what is most striking about this season is that we are now at the absolute peak of hurricane season, and there is simply nothing happening. Although the Atlantic season begins on June 1, it starts slowly, with maybe a storm here or there in June, and often a quiet July before the deep tropics get rolling in August. Typically about half of all activity occurs in the 14 weeks prior to September 10, and then in a mad, headlong rush the vast majority of the remaining storms spin up before the end of October.

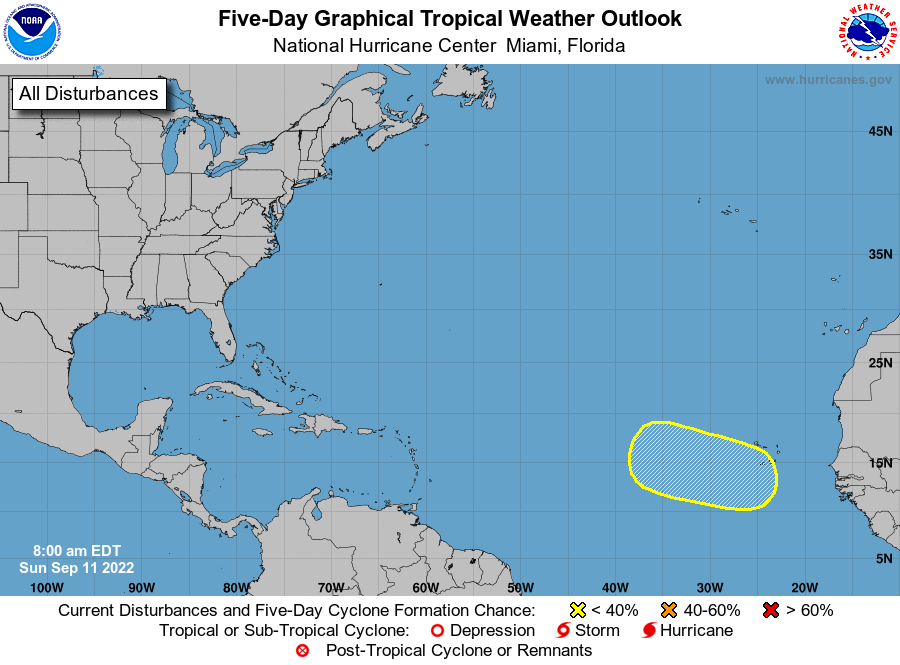

While it is still entirely possible that the Atlantic basin—which includes the Atlantic Ocean, Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea—produces a madcap finish, we’re just not seeing any signs of it right now. There are no active systems at the moment, and the National Hurricane Center is tracking just one tropical wave that will move off the African coast into the Atlantic Ocean in the coming days. It has a relatively low chance of development, and none of the global models anticipate much from the system. Our best global models show about a 20 to 30 percent chance of a tropical depression developing anywhere in the Atlantic during the next 10 days.

This is the exact opposite of what we normally see this time of year, when the tropics are typically lit up like a Christmas tree. The reason for this is because September offers a window where the Atlantic is still warm from the summertime months, and we typically see some of the lowest wind shear values in storm-forming regions.

What went wrong

So what has happened this year to cause a quiet season, at least so far? A detailed analysis will have to wait until after the season, but to date we’ve seen a lot of dust in the atmosphere, which has choked off the formation of storms. Additionally, upper-level winds in the atmosphere have generally been hostile to storm formation—basically shearing off the top of any developing tropical systems.

While it looks like seasonal forecasts for 2022 will probably go bust, it’s important to understand the difference between that activity and the forecasting of actual storms. Seasonal forecasting is still a developing science. While it is typically more right than wrong, predicting specific weather patterns such as hurricanes months in advance is far from an established science.

National Hurricane Center

By contrast, forecasters have made huge gains in predicting the tracks of tropical storms and hurricanes that have already formed. And while not as significantly, our ability to predict intensification or weakening has also been improving. Since Hurricane Andrew in 1992, the most destructive storm to ever hit Florida, the National Hurricane Center’s track forecast accuracy has improved by 75 percent, and its intensity forecasting by 50 percent.

This is due to several factors, including more powerful supercomputers capable of crunching through higher resolution forecast models, a better understanding of the physics of tropical systems, and better tools for gathering real-time data about atmospheric conditions and feeding that data into forecast models more quickly.