The failure of

Bernie Sanders to take control of the Democratic Party in the 2020 primaries

was understandably traumatic for the American left. Having rapidly ascended from

seeming irrelevance to surging media attention and organizing in just a few

years, many democratic socialists convinced themselves that their moment had

come.

Sanders’s loss

to—of all people—Joe Biden, therefore, came as a kind of cosmic joke. How

could it possibly be that a near-octogenarian, whose greatest legislative

achievements were pro-creditor bankruptcy reform and the 1994 crime bill, would

defeat the left?

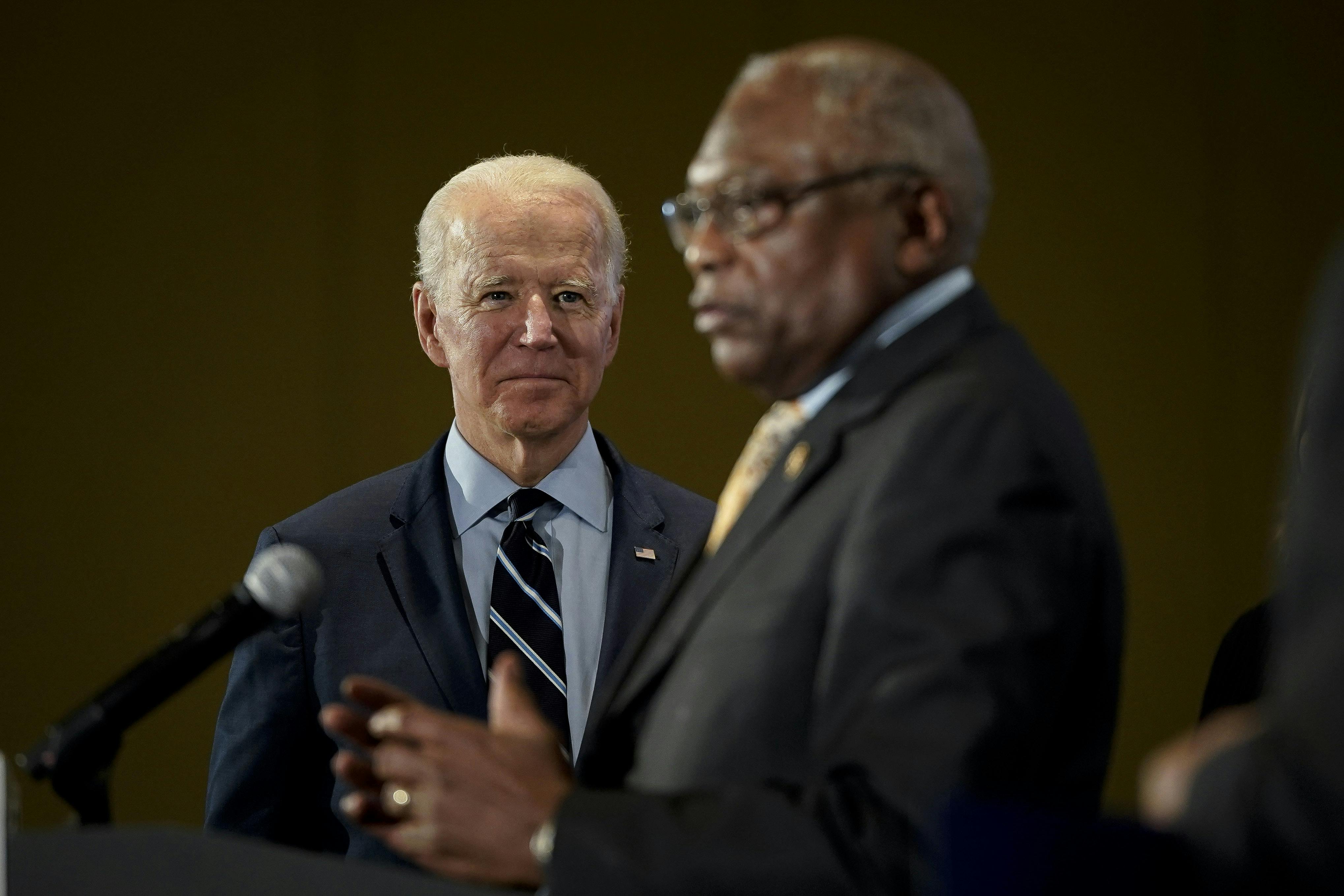

There was an

obvious explanation, of course. If you’re looking for the person who stopped

the Democratic Party’s movement to the left in 2020, that man is Congressman

Jim Clyburn. It was South Carolina, under Clyburn’s leadership, that turned the

tide, and it was the stubborn support of Biden by the older, more Southern,

more church-going parts of the African American community that denied Sanders

the nomination.

But for the democratic

socialists working to make sense of Sanders’s loss, there must be a more

psychologically comforting culprit. Yale professor Samuel Moyn, in his recent review in The New Republic of

our book Never Trump, thinks he has found one: Republican opponents of

Donald Trump. Moyn writes that “Sanders’s

decline had many causes, including his own mistakes, but it definitely mattered

that the Never Trump script treated him as mirror image of Trump, and as

equally perilous for ‘democracy’—and that many a liberal embraced this idea.” Yet

he provides little actual evidence that the Never Trumpers “mattered” other

than his assertions of their media influence. A few talking heads on cable TV seems

like a strange explanation for the behavior of largely African American voters

in Greenville and Beaufort, which, given the rhythm of the primary, is the

thing to be explained. The Never Trumpers may make an appealing scapegoat for the

left, but the far more obvious explanation for Sanders’s loss is the simple fact

that the Democratic Party is just not composed of enough voters (including, but

not limited to, African Americans) willing to provide a majority for democratic socialism,

at least in larger turnout elections.

Moyn’s essential claim is

that we served as easily duped mouthpieces for the Never Trumpers. “Saldin and Teles take a cozy approach to

their study of this movement and its central characters, faithfully drawing on

their accounts of the rise of Trump.” What Moyn characterized as “coziness,” we

think of as a rigorous, scholarly effort to try to convey the—inevitably

partial—perspective of our sources. We believe that the Never Trumpers cannot be

understood outside of the professional networks with which they were

affiliated. Moyn made only a passing reference to the central conceptual move

in the book, which is to understand the Never Trumpers as providers of

professional services to the Republican Party. The Never Trumpers we devote our

attention to were the kinds of people who provide policy expertise and key staff posts in GOP administrations, the political pros who run campaigns, and the

public intellectuals who provide ideas and guard the intellectual boundaries of

conservatism. Each of these professional networks has its own unique story to

tell in the Never Trump saga. Had we simply engaged in some armchair theorizing without actually delving into these networks, we would never have been able to

grasp many of the key factors that caused lifelong conservatives to oppose a

nominee of their own party.

Across these various

professional networks, a unifying theme emerged—both in our interviews as well

as in the contemporaneous materials we drew on, most notably a private email

chain of national security experts discussing a group statement denouncing

Trump. His Republican opponents have consistently told us—and told

themselves—that Trump is unacceptable because he is erratic, psychologically

unstable, ignorant, demagogic, dishonorable, and possessed of a disturbing sympathy

for the nation’s adversaries. Ideology and policy played a lesser role than did

character. Their obsessive focus on character may, in fact, be a fatal flaw in

the Never Trumpers, causing them to devote inordinate time to the president’s

manifest defects rather than developing alternative ideas and policies for a

non-Trumpy faction within the Republican party. Ironically, Moyn argues that “it’s

difficult to believe that Trump’s character foibles and edgy nativism are

supposed to explain the [Never Trumpers’] hatred for him” when it is precisely

the fact that they (with a few notable exceptions, such as David Frum, Yuval

Levin, and our compatriots at the Niskanen Center) are so focused on those

“foibles” that they’ve failed to productively engage in the ideological warfare

that Moyn seems to believe fundamentally motivates them.

Given that perhaps

excessive focus on Trump (and his apologists), it is puzzling that Moyn takes

us to task for failing to lay bare “all the Never Trump work that has gone into

helping centrist liberals win their struggle against the left in the Democratic

Party, a form of power even if they never get their party back.” To this claim

we can only say that we sincerely wish that Never Trumpers had done such

consequential work. Unfortunately, they have not been nearly as engaged in the

actual contest for control of either party as we wish they had been. Most of

their energy has been focused on cross-partisan efforts to defend democratic

institutions and defeat Trump in the 2020 election, rather than on building the

moderate wing of the Democratic Party or an organized faction within the GOP

with the power to check Trump’s (presumably) more competent successors.

There is no question that

many Never Trumpers have much to answer for in their pre-2016 careers, and we

have significant criticisms of how they have devoted their energies since the

election. But we also believe that both scholars and political activists are

more effective when they strive to imagine what the world looks like to those

in situations quite different from their own, rather than projecting

motivations onto them from afar. Real, flawed, flesh-and-blood people with

diverse circumstances and histories, seeking to find direction in radically

unfamiliar circumstances are, we think, far more interesting and more

surprising than straw men.