How Kids’ TV Got Way Too Normal

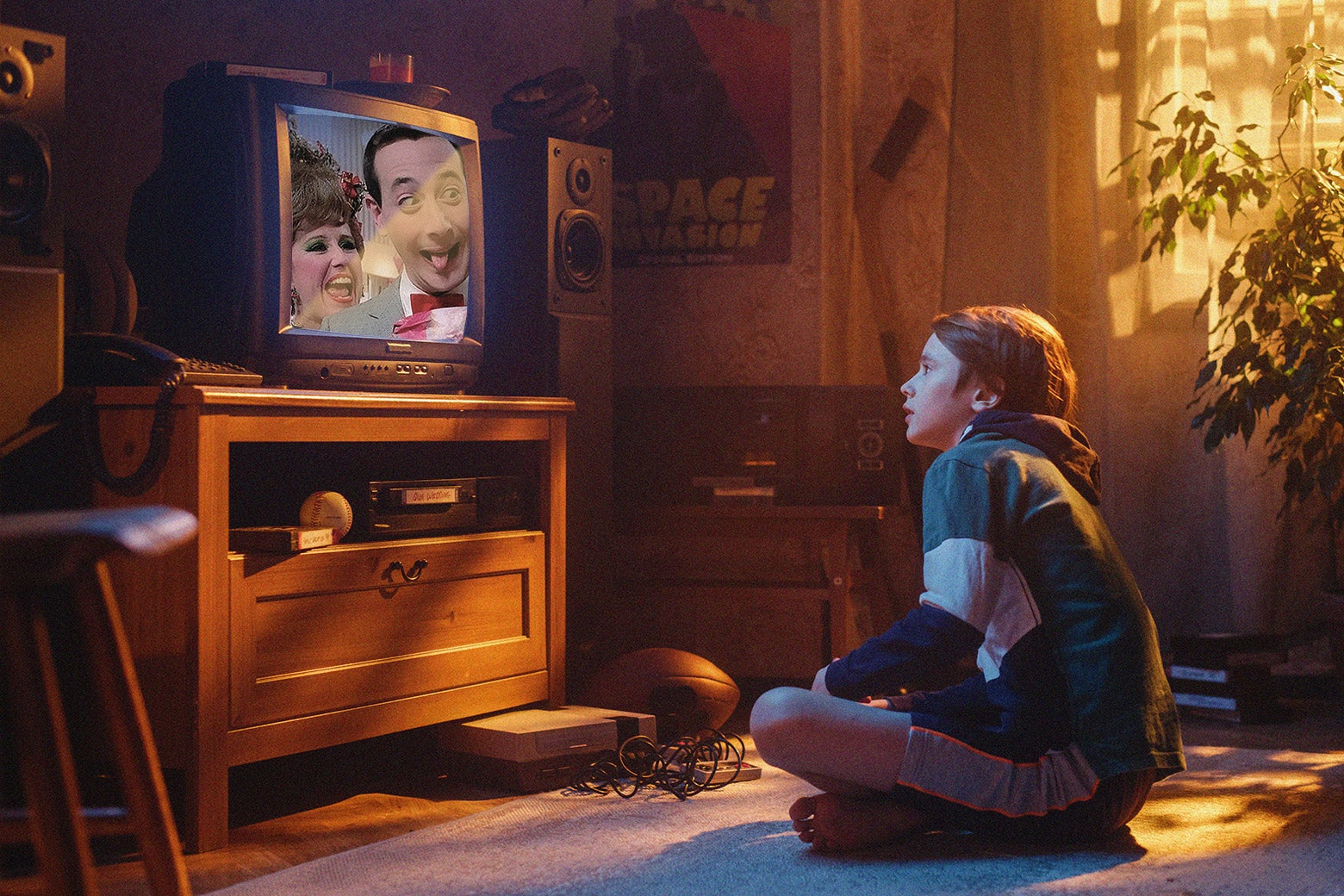

My son refused all age-appropriate movies and TV—until we went back to Pee-wee.

My son Levi, much to my frustration, has never been a big TV kid. For years, I’d put on an episode of Paw Patrol or a newish Disney movie, but nothing seemed to stick. Either he’d come to me halfway through to report he was bored or he’d be entertained enough to finish but would never request a second viewing or talk about it afterward.

I attributed this to a personality quirk or insufficient attention span, until the day, when he was 7, that I showed him Gene Wilder’s 1971 Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory. Now this “family movie” he loved. Same thing with The Wizard of Oz (1939). And then with an old children’s TV show, Pee-wee’s Playhouse (1986–90).

They say three is a trend, the rate of occurrence upon which one moves past the threshold of randomness and into the realm of fixed preference that we often identify as “taste.” Levi seemed to like older movies and TV. Levi seemed to dislike newer movies and TV. I sat down to watch an episode of Pee-wee’s Playhouse with him, and a hypothesis about why this is the case took shape.

All the movies and TV shows Levi is drawn to have a psychological ambiguity mixed with a psychedelic silliness that seemed hard to find in much of today’s popular kids’ content. Comfort alloyed with discomfort. Connection alloyed with loneliness. Heavy alloyed with light. Or, more succinctly, they were an accurate reflection of a day in the life of an average kid’s mind.

This made for a sharp contrast with much of the popular kids’ content I had earlier suggested and he had refused, entertainment that prioritized delivering easy moral lessons over observations on the eternal messiness of being human. And fair enough. It’s hard to teach right and wrong while also conceding how genuinely strange life is as a thinking, feeling human in relationship with other such humans. While this is the case for all of us, the veil between the conscious thought and subconscious urges is much thinner for children.

I was glad Levi had discovered an escape hatch from the clutches of didacticism that permeate the screen and the page these days. But I also wondered why it was content from the past that had helped him find his way out—and what kind of impact the apparent decline of playful, psychologically ambiguous works might have on his and other kids’ psychology.

The de-weird-ification of children’s media is part of a broader, complicated story. Back in the 1980s—the era of children’s media that I, a person born in 1979, am most nostalgic about—children’s television filled Saturday- and Sunday-morning time slots that otherwise held little value for networks. As such, creators had a fair amount of freedom to experiment without much meddling from higher-ups, Kyra Hunting, an associate professor of journalism and media at the University of Kentucky, explained to me.

This started to change for two reasons. First, Hunting notes, those higher-ups realized that they could license children’s TV characters and sell toys. Suddenly, more money was at stake, and with money comes risk aversion. Second, in the late 1990s, federal laws changed in a way that allowed for consolidation of ownership of media companies, leading to less variety and more pressure to perform for the sake of the bottom line.

Another shift that happened since the 1980s, Hunting says, is that children’s media became more age-specific. The rise of cable television in the late 1980s and early ’90s made room for more content, which made room for age segregation. Television for preschoolers became a thing, and TV shows lost some of the abstraction that makes programming appealing to a wider range of ages.

Fast-forward to the past decade, when global streaming services appeared, alongside the rise of YouTube and smartphones. We are all consuming content in this “second screen” era, during which producers of shows are told to keep things basic because people are probably reading their phones while watching TV. Meanwhile, the algorithms of streamers promote the most generically appealing, lowest-common-denominator content. Kids’ enthusiasm for this meh content, such as it is, is heavily reinforced by the toy aisles at Target, where merchandise for these widely consumed shows is abundant. One can purchase a Paw Patrol activity rug, a DC Comics deluxe figure set, a SpongeBob SquarePants interactive plush house, and countless other plastic and polyester iterations of the most popular entertainment franchises.

This doesn’t mean there weren’t uninspiring kids’ TV and movies in the pa