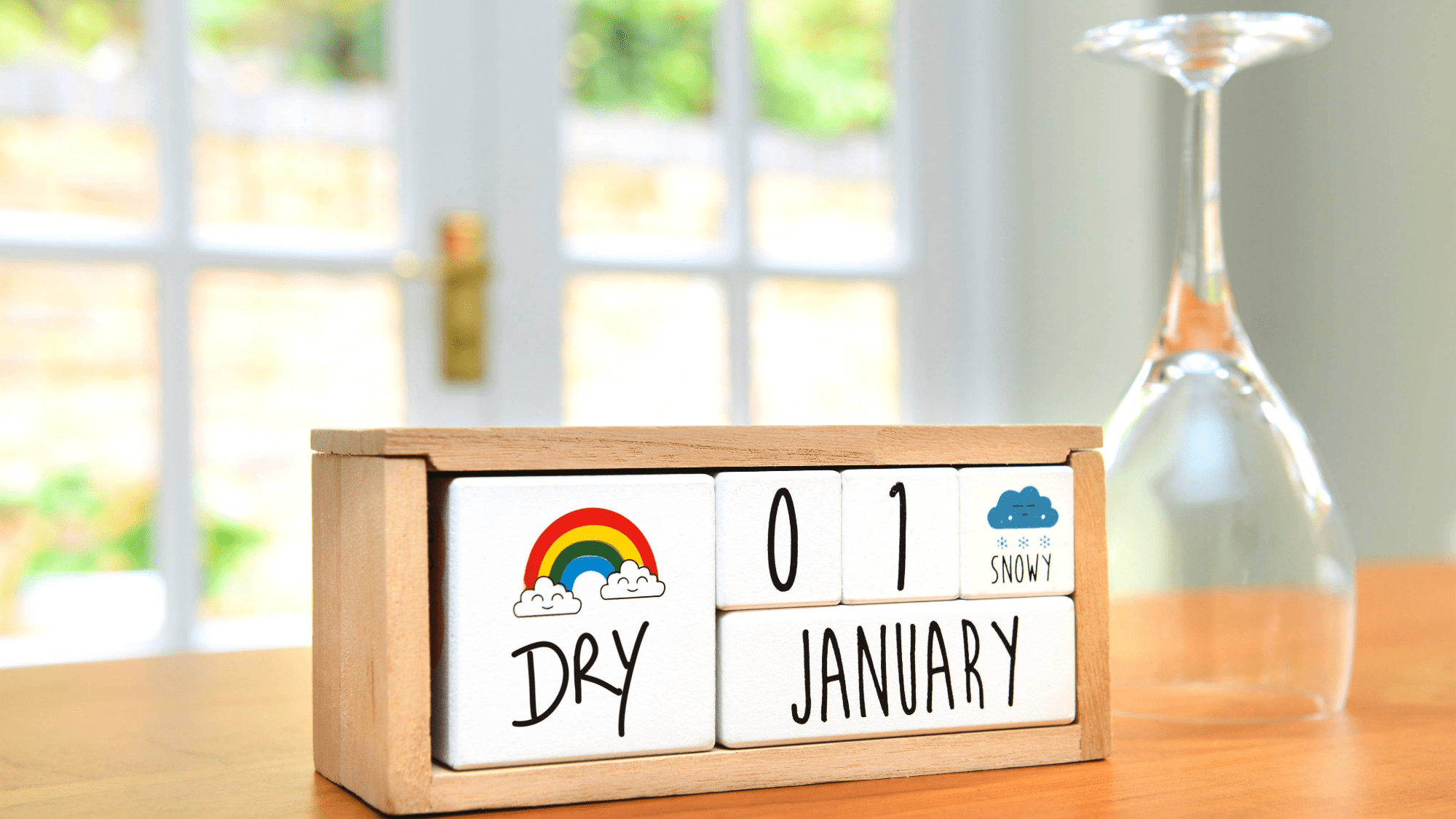

It’s a new year, which means it’s time to take stock of old habits. For many that means resolutions to get healthier and a month long break from booze, in observation of Dry January.

Yet as 2025 begins, what hasn’t changed is the muddled messaging over the health effects of moderate drinking. Two recently released federal documents offer contrasting perspectives on alcohol and health–underscoring a long-standing, ongoing scientific debate that’s reverberated through some of the most prestigious scientific journals and institutions.

A review published in December by the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine tows what some see as an outdated line: suggesting that up to a drink or two a day is associated with health benefits like reduced risks of heart disease and death. The National Academies’ analysis will likely inform revised national dietary guidelines set to come out later this year. (Current U.S. guidelines state that alcohol consumption should be limited to one standard drink a day for women and up to two drinks a day for men. This is also considered the upper limit on “moderate consumption” by many U.S. researchers and agencies.)

Then, on January 3rd, the office of the U.S. Surgeon General released an official advisory unequivocally stating that drinking alcohol, at levels as low as one drink per day, can cause certain cancers. The advisory calls for updating the existing health warning labels on alcoholic beverages to include a warning about the cancer risks.

So what gives? How can any substance be simultaneously associated with reduced risk of death and also increased cancer risk? How can big studies in well-regarded journals disagree on something as basic as harm or benefit? Why is the U.S. government seemingly arguing with itself? Is any amount of alcohol healthy?

Answers to all of the above are complicated. There’s statistical biases and confounding factors that muddy the data, the financial interests and outside influence, and a lack of consensus on how to define terms such as risk and moderate. Researchers sometimes disagree with each other about how to interpret the available evidence, and what guidance is best for boosting health. But there are some things we know for sure. Here’s what’s clear and what remains murky, when it comes to alcohol and health.

Consensus, straight up

Popular Science spoke with six expert sources for this article, including some who endorse the idea that moderate drinking may be associated with health benefits and those who say that drinking at every level carries only health risks. Every single source agreed that alcohol consumption exceeding one standard drink a day for women or two drinks a day for men can have negative health consequences, and that drinking beyond that level brings significantly increased risks of accidental injury and death, certain cancers, heart problems, liver disease, cognitive impairments, and more.

Internationally, the definition of a standard drink varies. But in the U.S. and Canada it’s defined as 0.6 fluid ounces or about 14 grams of pure alcohol, which is equivalent to 12 oz of a 5% beer, 5 oz of a 12% wine, or 1.5 oz of a 40% distilled spirit.

All sources agree that binge drinking, heavy drinking, and alcohol use disorder are serious public health problems, and none directly endorse starting or increasing alcohol consumption for any health reason.

“I wouldn’t want to recommend drinking, especially to someone who isn’t otherwise going to drink,” says Gregory Marcus, a cardiologist and professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. “Even if there are protective effects, which I acknowledge is possible, I don’t think that the level of evidence is high enough to recommend initiating it,” he adds. That’s despite his own, ongoing research trying to tease out potential heart health benefits of moderate drinking and his perspective that “light drinking may have salutary effects that are biologically plausible.”

Further, it’s firmly established that alcohol is an addictive substance with systemic effects in the body that can lead to physiological dependence. Use at low levels carries the risk of increasing and excessive consumption. Upwards of 20% of Americans who drink will experience an alcohol use disorder in their lifetime, according to data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions.

There is no debate when it comes to the harms of excessive alcohol consumption. Instead the ongoing scientific discussion is about how to research and classify the health effects of relatively low alcohol consumption and how to communicate to the public about those effects.

Increasingly, there’s also burgeoning scientific agreement that the risk-relationship for alcohol and certain cancers is straightforward: every additional volume of alcohol consumed is associated with increased risk of cancer. “Alcohol is a carcinogen. That link is very well established,” says Adam Sherk, a senior scientist at the Canadian Center on Substance Use and Addiction, an NGO founded and overseen by the Canadian government.

Different analyses disagree about what level of alcohol consumption poses what level of risk for what cancers. But even the new National Academies report, which critics say is conservative in its assessment of health harms, found a 10% increase in breast cancer risk among moderate drinkers compared with those who reported never drinking alcohol.

According to the National Cancer Institute (NCI), there is robust evidence linking moderate drinking with increased risk of head and neck, esophageal, colorectal, and breast cancers. Light drinking (variably defined, but loosely: a few standard drinks a week, and less than a drink a day) is associated with measurable increased risk of esophageal and breast cancers, per NCI.

Finally, sources generally a…