COVID-19-related lockdowns dampened human activity around the globe—giving seismologists a rare glimpse of the earth’s quietest rumblings. Christopher Intagliata reports.

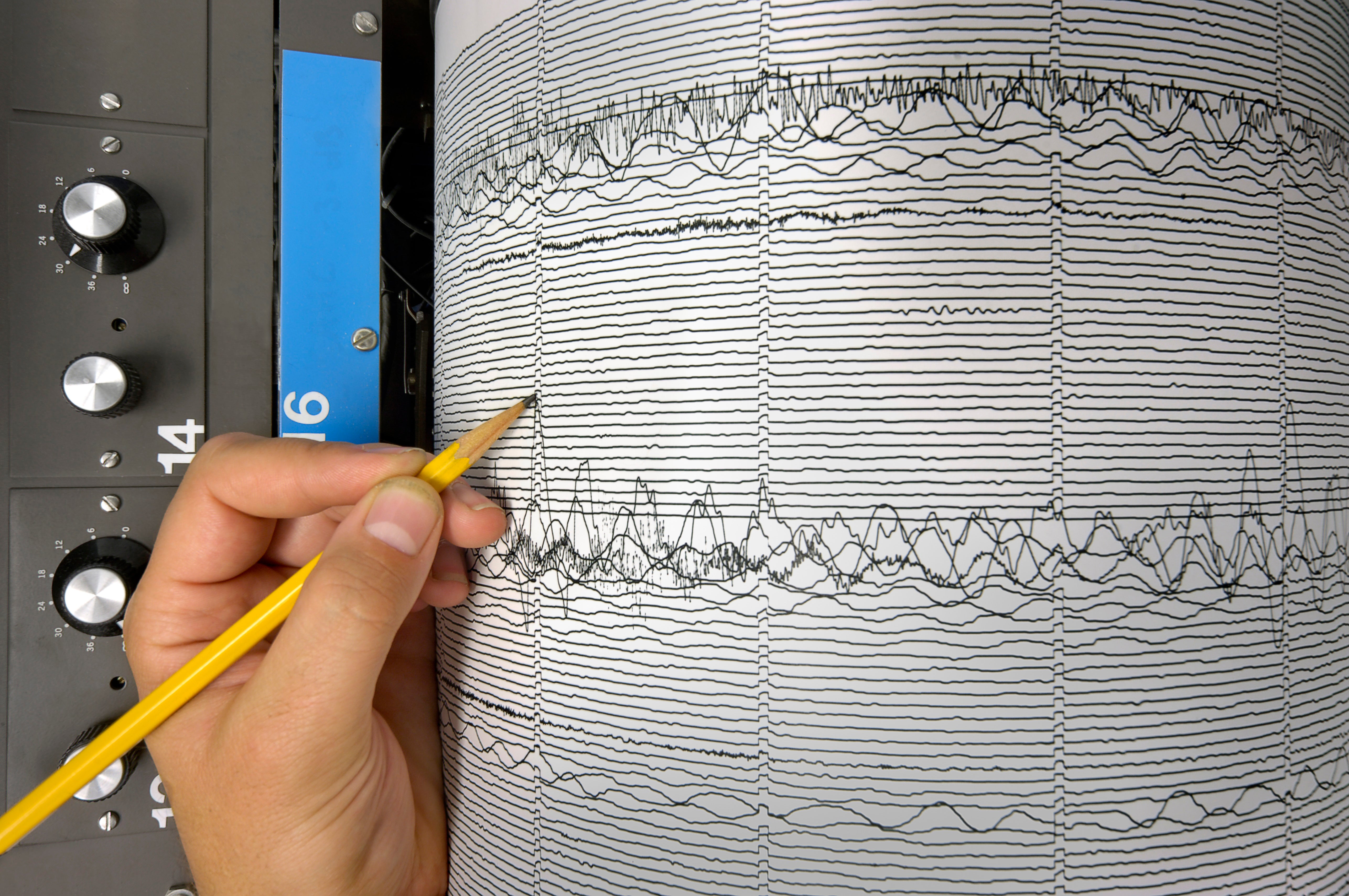

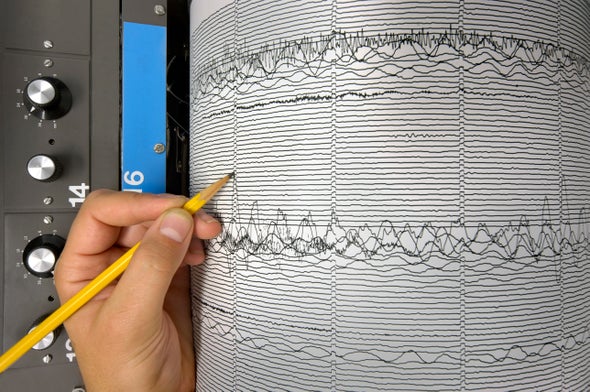

Humans are a really noisy species: hammering and digging, flying and driving, delivering heavy cargo all over the world. And that activity creates seismic noise, which masks delicate signals from faraway small earthquakes.

Raphael De Plaen, a seismologist at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, compares listening for small earthquakes during normal times to sitting at a wedding, at a table far away from the band. You can’t really make out the music, because there are so many people laughing and talking in between you and the loudspeakers.

“And so now the lockdown is like coming during the rehearsal—no one is talking. So even though you’re far away, the speakers are loud enough for you to listen to all the songs and clearly identify them.”

De Plaen says he and his colleagues have been able to detect “songs”— in this case, seismic signals—they didn’t even know existed. And now that they’ve identified those signals, they’ll be able to look back at decades of data and use these newly discovered seismic fingerprints to better identify small earthquakes like this in the past.

The study, co-authored by more than 70 seismologists from around the world, appears in the journal Science. [Thomas Lecocq et al., Global quieting of high-frequency seismic noise due to COVID-19 pandemic lockdown measures]

In addition to unmasking new seismic phenomena, the study also demonstrates how seismic data could be used to track human activity and movement—like traffic in a certain region, for example—and all without the privacy concerns that go along with cell-phone tracking.

“By definition, what we are observing is already anonymous—there’s no way to actually know if John Doe has left his home to spend the night in another place.”

De Plaen points out that this finding may be one of the only positive things to come out of the global pandemic: the ability to better detect future earthquakes.

— Christopher Intagliata

[The above text is a transcript of this podcast.]