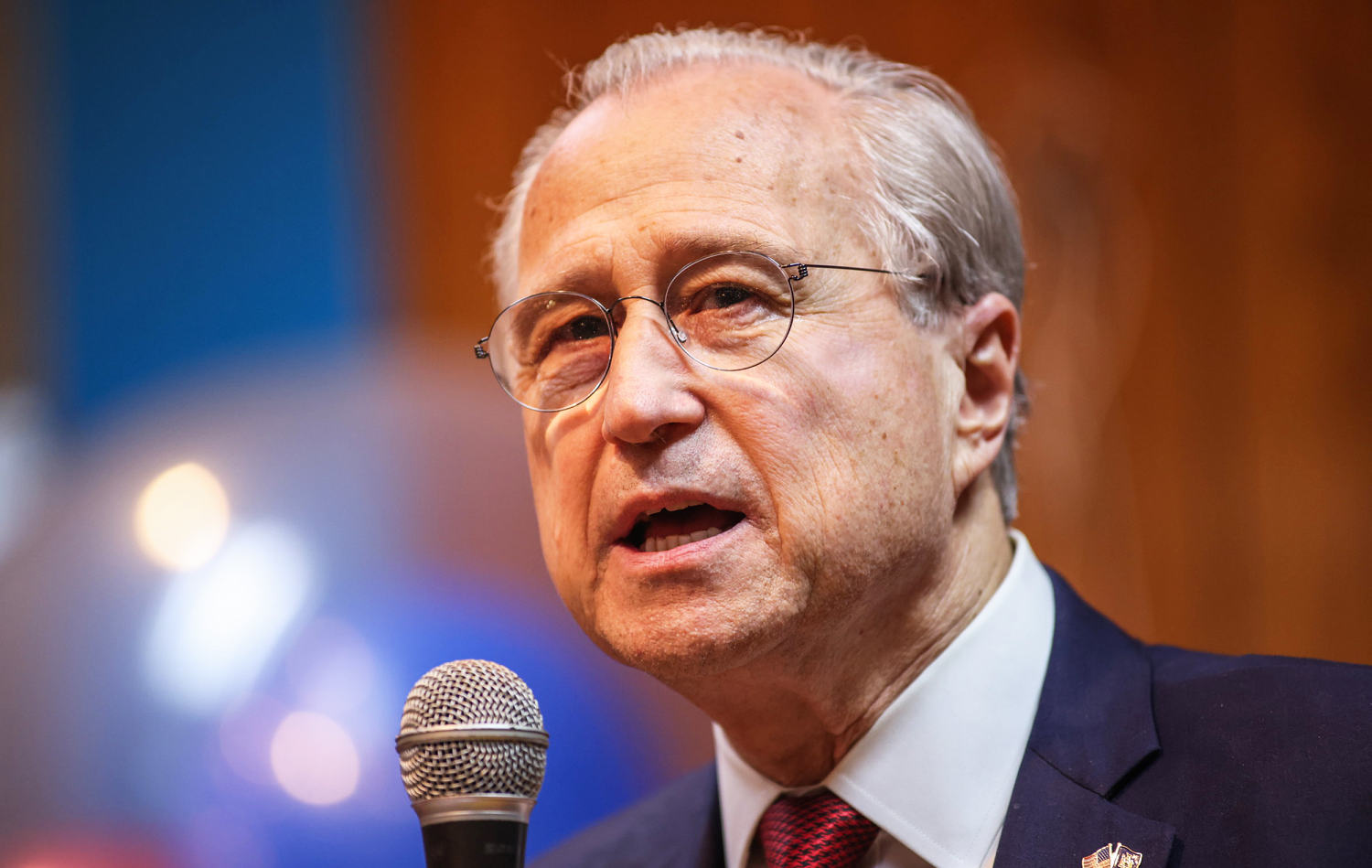

COPENHAGEN — Secretary of State Mike Pompeo touched down in Denmark on Wednesday for the first time since President Trump’s desire to buy Greenland caused a diplomatic spat and led to the cancellation of a state visit last year.

Many Danes remain suspicious of U.S. interest in the Arctic, and Pompeo’s meeting Wednesday with the foreign ministers of Greenland and the Faroe Islands underscored U.S. aims to build closer ties, while edging out competition from China and Russia.

“We are very worried that the Arctics will become a playground or a theater of war for the great powers,” Faroe Islands Foreign Minister Jenis av Rana told reporters before Pompeo’s arrival.

But Danish Foreign Minister Jeppe Kofod said any change in status for Greenland was not on Wednesday’s agenda.

“That discussion was dealt with last year,” Kofod said. “It was not on the table in our discussion.”

He added that the four foreign policy chiefs did talk about “how we can strengthen our cooperation on a whole range of areas.”

“We are, as I said, each other’s closest allies when it comes to security in the Arctic, North Atlantic, we are true partners, and we will continue to be that,” he said. “But we also have unexplored potential to grow trade, tourism, education cooperation and other types of cooperation between us.”

Pompeo met first on Wednesday with Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen — who last August dismissed Trump’s interest in purchasing Greenland, an autonomous island within the kingdom of Denmark, as “an absurd discussion.” Trump responded by calling her comments “nasty.” Pompeo had tried to calm tensions, calling Copenhagen to convey appreciation of a U.S. ally.

“When Donald Trump said he wanted to buy Greenland last year, it sent shock waves through the Danish government,” Kristian Mouritzen, a Danish political analyst, told The Washington Post. “It was close to becoming a very big problem for Denmark until Mike Pompeo helped Mette Frederiksen smooth things out with Trump.”

Pompeo reiterated that praise on Wednesday.

“Nowhere do we have a nation that will help us like Denmark,” he said. “Nowhere have we better upheld our shared values than with the Kingdom of Denmark and the great work we’ve been able to do on Greenland. Quite simply, it’s a new day for the United States and Greenland.”

He talked up the overtures the Trump administration has made toward Denmark’s autonomous territories.

Last month, the United States opened its first consulate in Greenland since 1953. “Reopening the U.S. Consulate in Nuuk reinvigorates an American presence that was dormant for far too long,” Pompeo said.

He also referenced the U.S. offer of a $12.1 million economic development package for Greenland.

And he added that the United States and Faroe Islands had “agreed to start a formal dialogue to talk about key issues like healthy fisheries and enhanced commercial engagement.”

The U.S. ambassador to Denmark, Carla Sands, has met with Faroe Islands officials to discuss opening a consulate there and the possibility of using harbors to support U.S. naval operations in the Arctic, according to Faroese media.

In March, Sands offered unspecified support to the Faroe Islands foreign minister to combat the novel coronavirus. When the offer became the subject of news reports in April, it prompted widespread criticism from Danish lawmakers, who noted that the Faroe Islands were doing better than the United States during the pandemic.

Denmark, too, has had success controlling the coronavirus pandemic. On Wednesday, upon his arrival at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Pompeo went to shake hands with the Danish foreign minister, who didn’t offer his hand back. Pompeo extended his hand to the Faroese foreign minister, who also would not shake hands. Pompeo then elbow bumped with the Greenlandic foreign minister before entering the building.

The broader theme of Pompeo’s trip, which first involved a stop in London, has been to encourage allies to stand with the United States against China.

“The U.S. wants Denmark and its autonomous territories to understand that China is more than just business, it’s geopolitics,” Sten Rynning, professor of international politics at the University of Southern Denmark, told The Washington Post.

“The reason Denmark is an important recipient of this message is because Greenland is so strategic. The U.S. does not want to let China have a free pass into the Arctic realm,” he said.

China, which defines itself as a “near-Arctic nation” — despite Beijing being almost 1,800 miles from the Arctic Circle — has invested heavily in Greenland’s infrastructure and its fishing and mining industry in recent years.

“Many decision-makers in Nuuk are warmly welcoming the increase in U.S. interest,” Martin Breum, an expert on Arctic affairs, told The Post. “But Greenland sells fish and shrimps for more than $230 million dollars every year to China. So Greenland is eager to hear from Pompeo that its relationship with China is not seen as problematic by the U.S.”

The fear is that competing interest from great powers could destabilize the region.

“The Arctic as a low-tension area is challenged by the U.S., Russia and China,” said Cecilie Felicia Stokholm Banke at the Danish Institute for International Studies. “There is an apprehension here that the Arctic will increasingly become an arena for international power politics and that’s what Denmark, Greenland and the Faroe Islands are seeking to avoid.”