“No matter how long a child has been missing, we’ll never stop searching.”

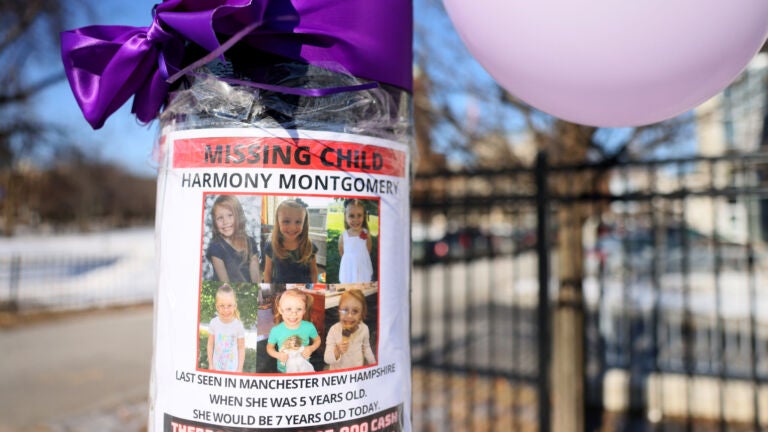

Harmony Montgomery was reported missing in November. Months later, investigators are still asking for the public’s help finding the girl who was last seen in 2019 when she was 5.

She is just one of thousands of children who were reported missing in 2021 and have yet to be found.

Though the data for 2021 has not been released, in 2020 there were 365,348 reports of missing children added to the FBI’s National Crime Information Center (NCIC), according to the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children.

That number represents the number of reports — if a child went missing more than once, they would be counted more than once.

Harmony’s story and picture has been widely circulated in the weeks and months after she was reported missing. But what about the scores of other missing children?

Some of the most urgent cases, such as when a child is in imminent danger, are reported to the public using an AMBER Alert, an emergency communication that goes to phones, TVs, radios, and more across the country, according to the U.S. Department of Justice. Other cases get pulled into the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children, also known as NCMEC, so the center can help law enforcement find the child.

Though the acronym NCMEC may not mean anything to most people, it is the same agency responsible for the milk carton missing person ads that first started in the 1980s. Its strategies have changed somewhat since then, but the center is still responsible for many of the missing child announcements people see in their day-to-day lives.

“With every missing child poster, that’s a call for public action,” John Bischoff, the vice president of the missing children’s division of NCMEC, told Boston.com. “That’s a call for public assistance to look at this image, this child is missing. Behind this picture is a family searching, a law enforcement agency working day and night to find this child. So please just stop and take a second look.”

NCMEC makes posters to hang in stores, designs files to display on billboards, and creates notices optimized for cellphones, among other methods of notifying the public.

But the lack of information available in these cases makes it difficult for law enforcement to share information with the public, Bischoff said.

“Law enforcement is coming in blind on this,” he said. “They’re learning as much about the child as they can, knowing that the child’s not here right now. The child’s not where they’re supposed to be.”

Bischoff said the photo is by far the most important part of a missing notice — most people won’t read, let alone remember, the information in the paragraph that often accompanies photos.

Because every case is different, with any missing person, organizations like NCMEC have to start from scratch.

They have a base to work off of, but can’t assume anything.

“Not one of them is just like the other,” Bischoff said. “There’s many different contributing factors, many different players involved. Law enforcement has a difficult task of really trying to dig in to figure out what’s going on here.”

NCMEC’s case managers reach out to law enforcement and offer any tools and resources the center has that may help the case. Bischoff said NCMEC partners with a lot of companies with cutting edge technology like genetic genealogy and DNA labs that can help solve cases, even if the case is months or years old.

“We work to coordinate resources with law enforcement and the parents and legal guardians of missing children, all with the goal of locating the missing children safely and as quickly as possible,” Bischoff said. “No matter how long a child has been missing, we’ll never stop searching.”

The cases NCMEC deals with are only a fraction of all missing cases reported, according to the center’s website. With the exception of children missing from state care, there is no mandated reporting to NCMEC. Rather, it is at the discretion of parents or guardians and law enforcement to report a case to the center.

Even so, Bischoff said the agency’s numbers in the past few years have gone up.

“When I started working for the missing children division back in 2010,” he said, “we were assisting with about [12,000] to 13,000 missing child cases a year. Our numbers just this past year, in 2020, we assisted with nearly 30,000.”

He added that the increase is not necessarily the result of more kids going missing every year, rather it is more due to better and more consistent reporting. In 2014, federal legislation went into effect that requires state agencies report a child missing from state care to both law enforcement and NCMEC within 24 hours.

In the last few years, NCMEC has seen many more reports to its CyberTipline, with more than 21 million reports in 2020, up from almost 17 million in 2019.

Bischoff said it’s hard to definitively say why children are going missing. The vast majority of cases NCMEC deals with have to do with endangered runaways, or a child under the age of 18 who is missing of their own accord.

Family abduction is the next most common classification, but the total is barely 5% of the number classified as endangered runaways.

In recent years, and especially during the pandemic, Bischoff said NCMEC has been very aware of online enticement, which can sometimes be a factor in why a child goes missing.

“Children may go missing, they may be listed as runaways and endangered runaways, but they may have left their house under false pretenses because they met someone online, which we see more and more of each and every day,” Bischoff said.

Support to End Exploitation Now (SEEN), a project run by the Children’s Advocacy Center of Suffolk County, has also seen a rise in online exploitation during the pandemic, according to Sheelah Gobar, the project manager for SEEN.

SEEN is a collaborative effort of more than 35 organizations that responds to cases involving youth who are either at risk of being exploited or confirmed to have been exploited. The nonprofit works closely with law enforcement, schools, mental health providers, and area hospitals to help create positive outcomes for child victims of commercial sexual exploitation.

The coronavirus pandemic also brought its own challenges to SEEN’s operations — a lot of the work relies on in-person interactions to help flag children who need help and then effectively assist them.

“There were certain mechanisms to locate a child that may have been adjusted in the beginning of a pandemic,” Gobar told Boston.com. “So even though we were working remotely, everyone was still able to stay in communication to ensure that use didn’t slip through the cracks and that we could re-strategize as needed.”

For missing children cases, SEEN often partners with NCMEC, according to Gobar. Together, the organizations strategize about how to locate a missing child or teen and safely engage them.

In addition to the rise in online exploitation during the pandemic, Gobar said SEEN has observed an increase in youth traveling out of state and more grooming techniques.

It’s more important than ever that parents and guardians are aware of what social media accounts their children are using, Bischoff said. He urged parents to talk about online safety with their children early and often.

“When we were growing up, my parents were telling us, ‘Watch out for the car and the white van … driving down the road,’” Bischoff said. “Nowadays, it’s coming right into our living room, right into our kid’s bedroom. It’s an internet connection.”

Often when a child or teen gets reported as missing, law enforcement and other involved parties try to find their social media, he said. He also acknowledged that some parents might find it difficult to have those conversations, pointing out that there is guidance on the NCMEC website for guardians on talking to their kids about social media.

“We’ve been telling parents for so long to watch over their kids’ shoulders and watch their activity online,” Bischoff said. “And then we hit a two-year period where online school was seven, eight hours — there was no getting away from it. There was no parent that was able to keep up with looking over their children’s shoulders for eight hours a day. … That’s a difficult route for any parent.”

Though many missing children never reach mainstream public consciousness, NCMEC won’t drop a case as time goes on. Cases such as Jaycee Dugard, who was missing for 18 years, and Elizabeth Smart, who was missing for nine months, prove that people can still be found years later, said Bischoff.

“There are these cases out there that allow us to grab onto the hope and understand that we may find this child one day and that’s what our hope is,” he said. “That’s what we’re going to live by, and that’s what we’re going to do day in and day out.”

Most cases are resolved within the first 24 hours a child is missing, but the numbers peter off as time goes on, he said.

Even so, Bischoff said they will “never give up hope on a missing child.”

He urged people to take an extra second to look at any missing posters or other alerts they come across. He said it’s easy for people not involved in the case to brush past posters, but they are an important part of the fight to find a missing child.

“Directly behind that image is a very scared family, a very investigatively leaning forward law enforcement agency, and a missing child who needs to be home,” Bischoff said. “No matter what the story is, no matter what the backstory is surrounding the child’s disappearance at that moment in time, each one of those posters is a call to the community to help us. Keep your eyes open, share the image.”

If you need to report a missing child, immediately call local law enforcement. NCMEC also recommends you call the center at 1-800-843-5678 and request that law enforcement enter information about the child into the FBI’s National Crime Information Center Missing Person File.

Other resources available include NCMEC’s online repository of all the active missing children posters in their system and Massachusetts’s list of missing persons reported by the state police.