In March, an Andy Warhol

exhibition opened at the Tate Modern in London. It was a European sequel to the

touring retrospective that bewitched the United States last year, but the Tate was forced

to close less than a week into its run because of Covid-19. When I imagine the

museum’s empty white rooms hung with all those Elvises and Maos, soup cans and

car crashes, flowers and skulls, I can’t help but think some perverse part of Warhol

would delight in a pandemic derailing his big show. His art, after all,

exploited the interplay of mass media and tragedy. Think of his prints of a

grieving Jackie Kennedy, or those eerie electric chairs and poisoned tuna fish

cans from the Death and Disaster series. Warhol’s DayGlo palettes and

celebrity faces can’t soften the underlying horror of his vision—the horror of

the twentieth century.

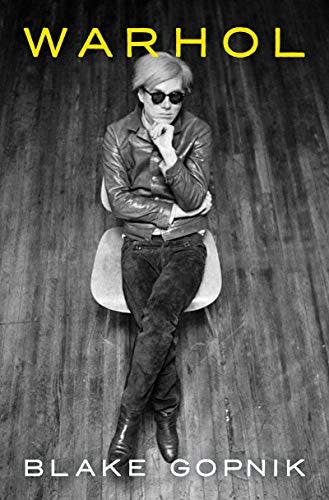

Warhol

by Blake Gopnik

Ecco, 976 pp., $45.00

It’s rare to think of

Warhol in such ominous terms today. His work, and Pop Art in general, is more

often viewed as ironic and effervescent, or as an indictment of American

consumerism. In his exhaustive new biography, Warhol, the critic Blake Gopnik

suggests that these misreadings snub Warhol’s deeper aesthetic and conceptual

aims. He quotes the art dealer Ivan Karp, who once said of Warhol’s work, “The

idea of doing blank, blunt, bleak stark images like this was contrary to the

whole prevailing mood of the arts—but it gave me a chill.” Gopnik echoes this,

arguing that Warhol’s repeating Coke bottles and Hollywood starlets are

“already images of disaster—or at least of a cultural death.”

Over the last

half-century, Warhol has been merchandised into the trite, plastic banality he

supposedly critiqued, but as Gopnik reminds us, the artist is much harsher, and

more cynical, than we sometimes credit. At nearly a thousand pages long, Gopnik’s

biography excavates many new or forgotten angles: Warhol’s love life; his

relationship with his mother, who lived with him almost until her death in

1972; his activism on behalf of AIDS—even his penis size and body hair get some

ink. Gopnik picks through the contradictory origin stories that surround

most Warhol enterprises, including his silk screens and Interview magazine.

There are conflicting reports about his whereabouts the day JFK was

assassinated. Even his oft-quoted maxim about how everyone in the future will

be famous for 15 minutes may be the work of some unsung copywriter.

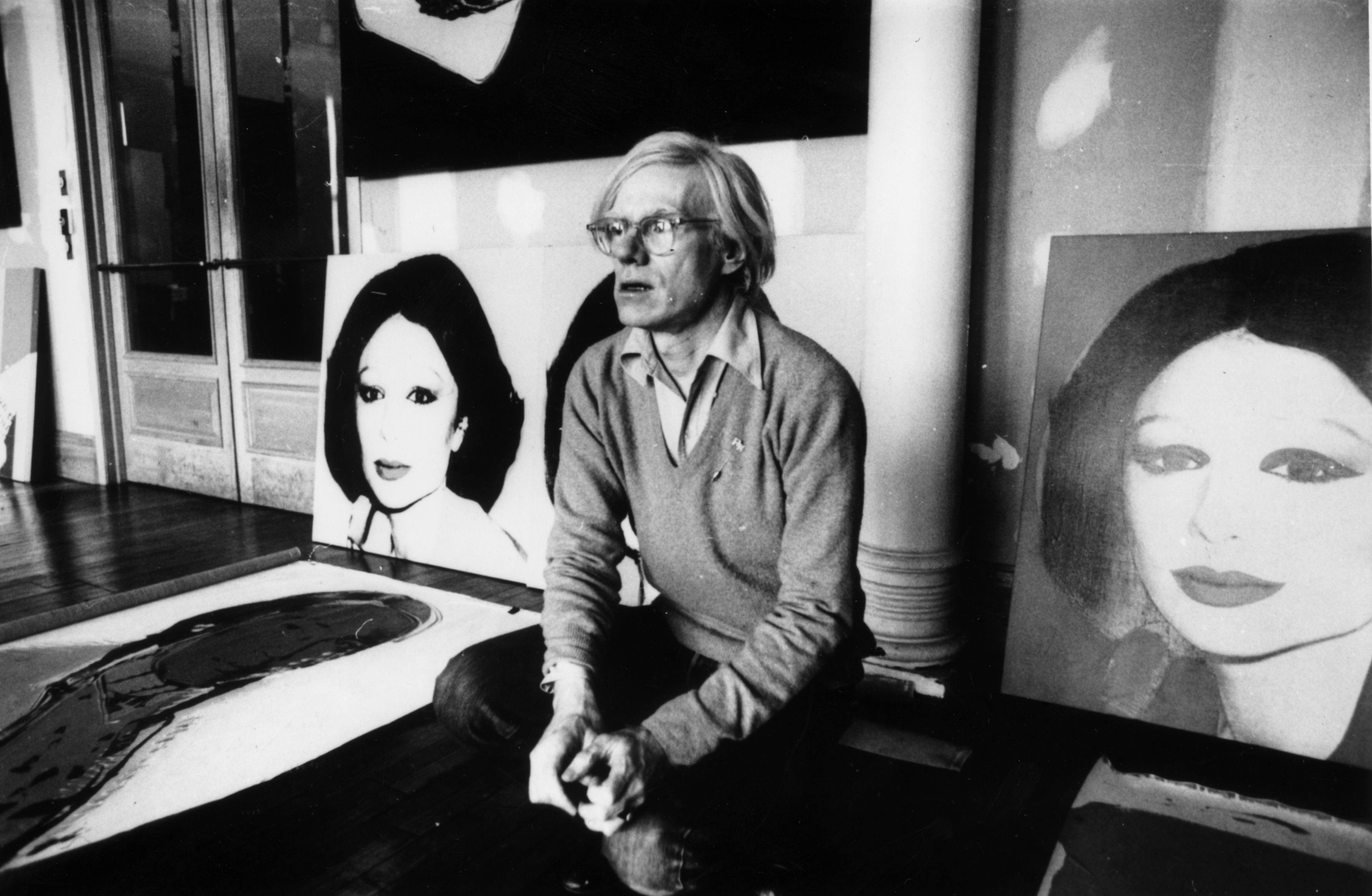

Warhol’s self-mythologizing

often obscured what a single-minded businessman he was. Gopnik’s book is partly

the story of how the art market exploded into the multibillion-dollar behemoth

it is today. Warhol’s career paralleled, and buoyed, the hyperinflation of art,

which became the metasubject of his work in the 1970s and ’80s. Warhol wasn’t

a bystander to all of this; he was a ruthless hustler and self-promoter who

squeezed every contact he had. His first silk screens, made in 1962, were of $1 dollar bills—a grid of cloned green cash that seems prescient in retrospect

but that then must have represented the half-joking ambition of an artist

several critics dismissed as a flash in the

pan.

Warhol is a notoriously slippery

subject for a biographer. Despite his many interviews and diaries, he

cultivated a deadpan blankness. The curator Henry Geldzahler said that Warhol

played up the “dumb blonde” schtick, and browsing some of the artist’s early

interviews, it’s clear how much performance

was part of his repertoire. One of his most infamous exchanges occurred at

the Stable Gallery, in 1964, when Warhol debuted his Brillo boxes:

Interviewer: Andy, do

you feel that the public has insulted your art?Andy Warhol: Uh, no.

I: Why not?

AW: Uh, well, I hadn’t

thought about it.I: It doesn’t bother you

at all then?AW: Uh, no.

I: Well, do you think

that they have shown a lack of appreciation for what pop art means?AW: Uh, no.

I: Andy, do you think

that pop art has sort of reached the point where it’s becoming repetitious now?AW: Uh, yes.

I: Do you think it should

break away from being pop art?AW: Uh, no.

I: Are you just going to

carry on?AW: Uh, yes.

Wayne Koestenbaum (who

wrote his own Warhol bio in 2001) notes that Warhol’s caginess is “poised

between happiness and sadness, between a speedy emptiness and a lethargic

fullness.” That ambivalence characterized Warhol’s whole artistic approach, as

well as his image. His iconic wig, sunglasses, and leather jacket remixed

masculinity and femininity into an asexual drag that nonetheless imparted the

erotic subtext of 1950s biker culture. Thematically, Warhol occupied “a middle

zone between establishment and underground, even at the risk of being scorned

by both,” Gopnik writes.

Few figures today toggle

between high and low, mainstream and alternative, radical and passé with the same fluidity.

This was by design and was arguably a byproduct of Warhol’s sexuality. As

Gopnik suggests, without the “tensions and complications” of his homosexuality,

Warhol “would never have become the great and enigmatic artist he was.” Even as

a successful commercial illustrator in New York in the 1950s, Warhol privately produced

delicate line drawings of boys kissing and embracing. In 1952, when he took

that work to the Tanager Gallery, an artist co-op in the East Village, the

gallery told him it wouldn’t associate with such louche pictures. (Earlier that

year, at another gallery uptown, Warhol had a short-lived exhibition of art

inspired by Truman Capote; the show was panned.)

Like many gay men then

(and now), Warhol invented his identity from matinées and Hollywood tell-alls.

He was born Andrew Warhola in Pittsburgh, in 1928, the fourth child of

working-class immigrants from Austria-Hungary. His parents were devout

Byzantine Catholics, although, as Gopnik notes, Warhol was less religious than

some accounts suggest. (He observed Good Friday of 1977 by screening Carrie.)

Two events from his

childhood cast long psychic and artistic shadows. The first was a bout of

rheumatic fever that progressed into Sydenham’s chorea (then called Saint Vitus’ dance), which Warhol suffered at the end of third grade. The condition caused

rapid, involuntary muscle spasms. According to Gopnik, rheumatic fever in

children may also correlate to psychological disorders later in life, including

obsessive-compulsive behaviors and body dysmorphia, both of which Warhol

manifested. His splotchy skin, in particular, tormented him.

The other event was the

death of his father, when Warhol was 13. This potentially contributed to

Warhol’s lifelong dread of doctors and hospitals; at the very least, the

Carpatho-Rusyn funeral custom of displaying the body at home for three days

disturbed the young artist. (As an adult, he skipped the funerals of his mother

and many of his friends.) The idea of displaying tragedy was one Warhol seized on throughout his career, not only in the Death and Disaster series but

also more personally. After he was shot by Valerie Solanas in 1968, he posed

for photographer Richard Avedon, capturing for posterity the crosshatched scars

and dimpled wreckage of his brush with death. It’s pointless to psychologize,

but Warhol’s early immersion in disease and death surely made those themes more

natural creative preoccupations.

Gopnik’s book briskly

covers Warhol’s years as a student at the Carnegie Institute of Technology. The

budding artist is depicted almost as a prodigy, intelligent and observant, but

also “very shy and cuddly, very much like a bunny rabbit,” in the words of a

college friend. As for his art, “He never had the innate talent for realistic

drawing that even many minor artists have,” Gopnik writes. What he did have was

an innate sense of style, and even playfulness, that caught the eye of art

directors when he stepped off the Greyhound to New York in 1949.

Gopnik evocatively

chronicles Warhol’s heyday as the city’s go-to footwear illustrator, but the

bio doesn’t really hum until the 1960s—the Factory years. This is when the familiar

pop culture iteration of Warhol took root, the pneumatic blond sphinx who made

all those silk screens and interminable movies, and whose entourage was a roving

madhouse of New York freaks. Although it’s cliché

to suggest that Warhol’s greatest creation was his own persona, it’s also unavoidable.

Warhol concocted a public image that was “unstable, incoherent, and often

opaque or off-putting to its witnesses,” Gopnik writes, adding that Warhol’s

personality itself was a work of modern art. Gopnik even pinpoints 1965 as the

year Warhol transformed from a “gum-chewing elf spreading smiles through the

land” to the more evasive “King of Cool” that still defines his image.

Warhol’s personality

wasn’t art, nor was his performance of personality art; his performance

of anti-personality was art. In this sense, he was more alienating than

Salvador Dali, whose outrageous antics and antennaed mustache had made him the

century’s other madman genius. Coming right after the boozy machismo of the abstract expressionists, Warhol, with his calculated vacuity, was

unclassifiable. Every new gallery show and gnomic utterance seemed to undermine

the seriousness of art as an endeavor. Gopnik connects Warhol’s superstars—the

raffish groupies who appeared in his movies and accessorized his parties—to

Marcel Duchamp’s urinal, the readymade object that rocked the art world in

1917. Just as that was a “found object,” Warhol’s Factory coterie consisted of

“found people.”

The final phase of

Warhol’s career was the longest and most checkered. Business Art, as he called

the work produced in this era, entailed portrait commissions from anyone with a

checkbook. Warhol painted corporate bigwigs and the Shah of Iran; he courted

Donald Trump and Imelda Marcos; he hobnobbed with Roy Cohn. Gopnik doesn’t make

a convincing case for why these portraits were anything other than paydays to

fuel Warhol’s shopping addiction. He trots out the musty comparison to Goya

painting the Bourbon nobility in Spain. “Warhol’s portraits could, and still

can, seem to have a critical edge when contemplated as one serial project—as an

inventory of human commodities, not tomato soup this time but lobster bisque,”

Gopnik writes. That implies Warhol thought of his commissions in moral as well

as economic terms, but Gopnik provides no evidence of that.

And that brings us to

the desolate terminus of Warhol’s project. Under his anesthetized gaze, ethical

subtleties collapse: An autocrat and a bottle of soda can hang side by side on

a museum wall in a hollow pretense of democratic art. Warhol’s morality was

for hire. His late work represents the “anything goes” ethos of capitalism that

was his overarching subject, as well as his livelihood. The critic Gary Indiana

said it best in his obituary for Warhol in The Village Voice: “An artist

of Warhol’s affluence isn’t faced with starvation if he turns down a

commission, say, from Idi Amin, or the Sultan of Brunei. Contrary to the Warhol

philosophy, modern life still does require choices.”

Gopnik isn’t particularly

interested in Warhol’s moral deliberations. Just as the artist leveled ethical

distinctions into particolored mulch, Gopnik breezes through Warhol’s indiscretions.

In 1969, for example, Warhol bought a studio complex in the Bowery and evicted

its artist-tenants; he never used the space himself. When he rented the

property to his friend and collaborator Jean-Michel Basquiat in the early 1980s,

Warhol worried what would happen if Basquiat turned out to be “a flash in the

pan” and couldn’t swing the $4,000 monthly rent. Other examples abound: Warhol

filmed Emile de Antonio guzzling a quart of scotch in 20 minutes for the 1965

film Drink, a feat that left de

Antonio senseless in front of Warhol’s voyeuristic camera. He once wondered if

Edie Sedgwick would commit suicide for him on camera. Even after all this,

Gopnik concludes the book on an adulatory note: “If we’re tempted to see the

common decency of Warhol’s final years as a late-in-life conversion to virtue,

that may be because we’ve failed to understand that he was decent all along.”

Gopnik’s bio tends

toward hagiography. One minor example: He writes that Warhol’s collaboration with

the three transgender actresses Candy Darling, Jackie Curtis, and Holly

Woodlawn helped the artist “stake an early claim to a post-Stonewall culture

where being swish became swank, as gay culture moved out of the closet and into

the disco.” This strikes me as an overly generous interpretation of Warhol’s

role in gay liberation. For one thing, Gopnik acknowledges that Warhol treated the

trio “as useful social props” rather than as real friends. Warhol’s 1975 series

Ladies and Gentlemen, which featured

portraits of cross-dressers, drag queens, and transwomen (including Marsha P.

Johnson), is arguably more revolutionary. But even here Warhol’s contribution

was complicated. The idea for the series came from the Italian dealer Luciano

Anselmino, who paid Warhol $1 million for the commission. The artist

dispatched his right-hand man, Bob Colacello, to recruit Black and Hispanic

subjects from the Gilded Grape bar in Greenwich Village. Each subject was paid

50 bucks for her half-hour sitting.

Gopnik is also

hagiographic about Warhol the artist, which is more cloying. “At his best,

Warhol didn’t think outside the box. He thought outside any artistic universe

whose laws would allow boxes to exist,” Gopnik writes. That’s the kind of

stoner koan you expect from an art school student, not from a professional

critic. Elsewhere, he claims that Warhol’s lackluster camouflage paintings were

“so strong and so smart they pretty much put him in the lead” of 1980s art. Anyone

familiar with 1980s art can furnish their own counterexamples of who was really

in the lead, whatever that means.

Gopnik’s book is rife

with such clunkers. Some of them are baffling, as when he suggests that one

early indication of Warhol’s sexuality was when the young artist ate only half

of a meat-and-French-fry sandwich from a famous Pittsburgh lunchroom. Is that really

a sign of queerness? Some of the writing is regrettable. Gopnik notes that the

first-prize pictures at the Carnegie’s 1941 exhibition “depicted lynchings and

other troubles of the American South,” as if lynching is an irritant on par

with, say, high humidity. He describes Solanas as “far from being your average

homeless person”—a line that radiates condescension and presumption. Other

sentences have about as much weight as Styrofoam: “It’s also clear that

[Warhol] was as sharp as could be, as was obvious to people who got really

close.” Still others are just plain dumb: Chelsea

Girls “foreshadowed the A.D.D.” of smartphones. Gopnik also has a habit of

quoting sources without naming them: “a famous critic wrote,” “as one

art-critic friend of his pointed out,” “in a Q&A with a notably silly

journalist.” In a book already verging on a thousand pages, why not just name names?

Ultimately, what’s

missing in Gopnik’s book is a clearer perspective on Warhol’s mature years,

when he personified art market excess. For my money, the most honest book of

the twentieth century is The Andy Warhol Collection, the six-volume auction

catalog Sotheby’s published in 1988. Ostensibly an illustrated guide to the

10-day, 10,000-lot estate auction held in New York the year after Warhol died,

this vast compendium is really a window into the artist’s compulsive

materialism. Warhol shopped two or three hours a day, cramming his Upper East Side

townhouse with a collection that included the valuable (art, jewelry,

furniture, watches), the esoteric (a stuffed bobcat, a Japanese suit of armor),

and outright kitsch (cookie jars, a vending machine, vintage board games). His

hoarding represents the quintessential rags-to-riches story, but also the

endgame of capitalist magical thinking, in which consumerism is a lonely

bulwark against death.

But death finally came for Warhol, too, leaving

those who knew him best with a bittersweet hangover. Judging by the many

memoirs and documentaries that have appeared since 1987, the jury is still out

on whether Warhol was an asshole, a saint, or both. Does it matter? His

artistic legacy is secure, in part because he recognized the durability of

cynicism. Gopnik, quoting Warhol, notes that truly modern art is without

feeling. This may be Warhol’s great insight. Nihilism never goes out of

fashion. Sometimes it even looks fun.